A Webex Diary

Notes From Watching Online

Originally published September 29, 2025

By Debbie Nathan

July 2025

For eight days now I have been low with an illness that my doctor has diagnosed as Covid, though the two tests I took at home – granted, they were leftovers from the pandemic and long ago expired – came up negative. “It doesn’t really matter,” the doctor said. “Upper respiratory viral (most likely) – whatever, and the protocol these days, whether Covid or not, is the same: 24 hours after your symptoms go away, you can go out and not be contagious.”

Eight days now with raw pain in the throat, hot flushes to the skin, and a shameful feeling of mental confusion. Perhaps it’s because I spend this sick time in a place that gives my symptoms an ambiguous etiology--in New York City immigration court, watching raw heated shameful rituals that end with hapless new Americans grabbed by those agents in masks. What is it with me? Psycho-? -Somatic? Corona-? -Virus? Who knows.

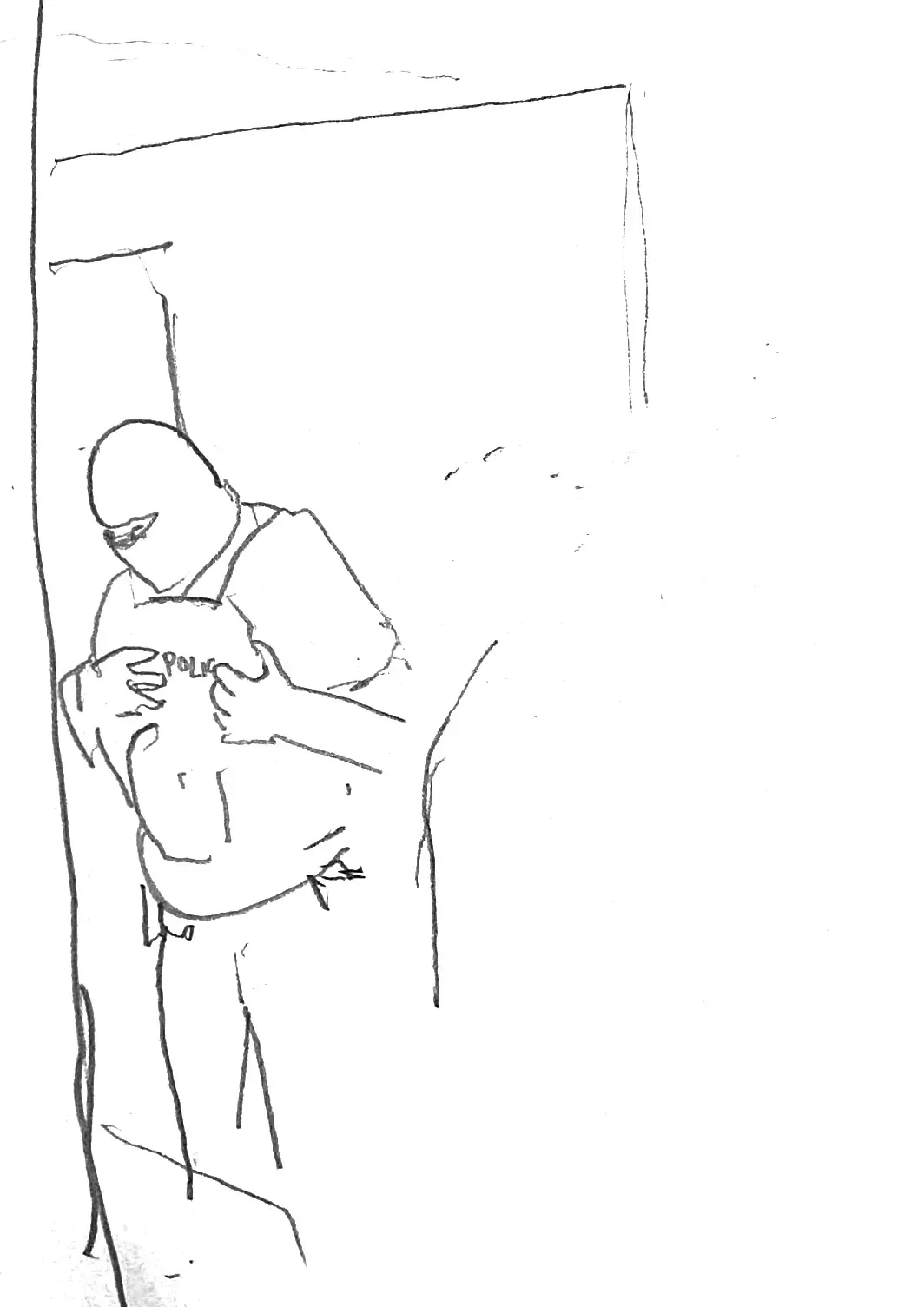

“Kidnappings!” say the immigration activists: those Good Samaritans who are models of leftwing praxis for Brad Lander. Some call the victims of ICE their “compas.” In truth, this is hard for me: they don’t speak much Spanish and don’t seem to know that this word in Latin America for deep friendship is used only by men with men, and I am not a man. Others call them their neighbors. But I have had personal friends, people I know and love, some of whom live very close by, who have lately been taken by ICE, and the grief and worry I feel is overwhelming. The first time I went to New York City court in person, on the Q train then the J and then the bowels of a Federal building and saw people being snatched by the agents of my state, muscled people in balaclavas who look as though they are made of dull, hard metal, and I felt the grief and worry all over again and couldn’t sleep all night and next day had to miss work. I decided then to do my activism virtually, so I wouldn’t have to see the snatchings, and now that I am ill, this virtual thing works out even better.

Yes, you can Zoom in real time into the immigration courtrooms, as you can inany such court in the whole country. It’s not Zoom, actually – it’s a Zoom doppelganger platform called Webex. And you can do what you did back during scary Covid, when you were trying to act businesslike for your job. You can put a suit jacket, decorative scarf and earrings on the topmost part of your body. And below the waist, sweat pants, pajama pants, no pants. Barefoot.

Now, five years after Covid, the immigration judges sometimes ask what you’re doing inside their courts on a screen instead of in person. But you are in your nice half clothes and many judges accept that the public has a right to watch them. Many nod when you mention this is your right and then forget all about you. You extinguish your camera and put your mic on mute.

You pour a cup of coffee and watch hours of senseless and sadistic proceedings, larded with high legal cant and low, US-Mexico border ports-of-entry names like “LUKEVILLE,” “EAGLE PASS” and BROWNSVILLE.” The goal of this arcane wording is to justify the physical seizure of our newest people so they can be hustled from sight and expelled from their and our American lives. Via Webex, I’ve glossed the vocabulary of this cruelty while sitting at home on the toilet.

It is afternoon after a morning in Webex court and my temperature is 99.5. That might sound low, but it’s two degrees higher than my body’s habitual measure, and I feel the extra heat. It is making my mind feel vague. I have spastic urgings to cough.

On Webex I see something in a courtroom. The judge seems no better or worse than most of his colleagues whose proceedings I’ve attended. He recites the immigrants’ names and asks them curt questions. He asks if they have questions for him. Few do. He assigns them future dates in court.

Some immigrants seem so sprightly and are so quick to answer, so on point. Others are skittery or slow or sad. One woman looks young but her brow can’t break its furrows. She tells the judge she has not filed her complete paperwork for asylum on time because she recently given birth and sank into deep depression.

The woman is on Webex, like me. The visual backdrop to her quiet confession of mental crisis is a cheap standup lamp with its wires snaking around, and an ironing board. The judge takes pity and gives the furrowed woman an extension. Listening to their dialogue makes me flush. I put the thermometer in my mouth.

The ironing board marks her long geographic distance from the court building and its predation. The ironing board is her amulet to prevent kidnapping. My own ironing board is in a closet and I hide my snaking wires in a tasteful box made of bamboo.

I missed work yesterday and called in today to say I’ll miss tomorrow: the fever. I teach a drop-in English as a Second Language class, to the same kinds of immigrants that ICE is going after. The week after the inauguration, I lost three-quarters of my students. They’ve drifted back, mostly, except for the Haitians and Venezuelans. In February I was instructed by my supervisor to mount a paper sign outside the thick, oak door: “This Class is Closed to All Except for Students.”

I worry what I will do if ICE tries to barge in past that sign. I imagine furiously shaking my fist and booming my voice. I used to dream the same thing in my twenties, except back then – this was the early 1970s—the dream was about addressing a revolutionary rally.

I’m worried that missing multiple days of teaching will shrink my classes even more. Maybe the students would not care so much about my illness if I wore a mask. But what do they think about masks these days, when everyday monsters wear them? I bring fruit to my class and we enjoy it while we work on our irregular verbs and the names of basic foods. Several of them are day laborers who hang out on the street for hours everyday to obtain work. I worry so much.

I’m trying right now to decide if I should take two Advils or just ride out this low-grade temperature. A South American woman is physically in the room. She is describing to the judge how she was terrorized by a mafia in her country and fled in the dead of night, leaving behind multiple children, who are now ill, and she wishes to self-deport so she can go care for them, and can the judge assist?

The judge hems and haws. “Voluntary departure. I can do that right now for you…But Ma’am, you may want to just go home and think about it…I’m giving you a return hearing date for a few weeks from now…come back then and let me know.“

“Thank you, Your Honor, thank you. I will see you then.”

The details of this woman’s immigration history—the precise date when she entered the United States and the place where she did so—sound ominous to me. According to the latest edicts from Stephen Miller, she clearly is vulnerable to be taken by ICE.

I send a text to some people I know inside of the court “Woman, Spanish speaker, coming out now.” They will hurry as the door opens and they will try to walk her to an elevator, then to safety from this nightmare building.

She leaves.

Minutes later, I learn that despite efforts to escort her out safely, the woman was taken. I do not ask for details. A memory of her Webexed face is sufficiently indelible: hopeful, serious, terrified.

I take 400 mg. of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication. On Webex, no one sees me swallow.

August 2025

Sitting at home on Webex I wander by accident into the kind of hearing where the asylum seeker finally presents all their testimony, photos, declarations, affidavits, news clips and witnesses -- to persuade the judge that something awful happened in the home country, and going back there would be dangerous to downright deadly.

The judge and ICE attorney are both physically in a courtroom in Lower Manhattan--the courtroom I’m watching from afar. Like me, the asylum seeker is on Webex.

He presents with the clothing, speech, and mien of an intellectual. He speaks a language I can’t place, though I do hear a smatter of Arabic words I recognize. He is about 70 years old. His face is that of someone who has lived a life of bookish precision.

The government attorney is one of those thirty-something white women in their navy jackets and little heels. She’s a type in these courts. They all have long hair. They part it in the middle. Many have slight Valley Girl or Upper West Side accents. A recent academic study I read about ICE lawyers notes that, whereas ICE removal officers -- the people who mask and tattoo up and grab the immigrants and stuff them into elevators -- are mostly working class Latino males, the ICE attorneys are mostly white females like this one, most of them Democrats, independents, or left-liberals.

I usually see these attorneys during “master calendar,” i.e. preliminary, hearings. They are pretty quiet then. They seem almost shy. “Yes, judge.” “No, your Honor.” Their speech is soft and formal.

In this very different hearing, the final hearing, the elderly immigrant is talking about leading a pro-LGBTQ protest and then being assaulted, and he and his family being threatened with violence, and, he says under oath, feeling they could not safely stay in their country.

I don’t know what country that is.

It’s clear that by the time I landed in this proceeding, the man with the face of chiseled grooves is in the middle of a cross-examination by the smooth-faced young ICE lawyer. The shy little preliminary hearing style which I so often hear from these women has been replaced with crude barks directed at the asylum seeker, and dripping titrations of sarcasm.

“And nobody from the GOVERNMENT harmed or threatened you. RIGHT?”

“No.”

“How come you didn’t mention any of these “threats” in your STATEMENT?”

“How come” instead of “Why.” Slang instead of the language an ICE lawyer uses to speak to a judge. And you can hear the air quotes.

The asylum seeker misses a few beats.

Who can really know the truth of this case, except for the man with the lined face who is 35 years his prosecutor’s senior?

And who among this courthouse of federal inquisitors, whose job it is to represent our government, really cares about the facts. Inquisition is what they learned in their law schools: Fordham. Hofstra. Brooklyn Law. Cardozo. Columbia (I know where this one studied, from looking her up on the Web.)

She probably voted for Kamala.

Suddenly the whole Webex screen blows up then goes black. Someone in the court has suddenly realized there is an interloper in the hearing. Suddenly I’ve been kicked off.

Drawings by Izzy Barber