A Good Day at Immigration Court

“I can get you some coffee,” I said.

Originally published on November 2, 2025

By SEB

We charged into the immigration court waiting room, eager to help. It was about half full. I’m a middle-aged white woman, and this was my first day visiting immigration court. My wife, a veteran court watcher, said things looked good: there were no ICE agents outside the room. She sat down next to a young Latino couple and began chatting with them in Spanish. Decades ago I had studied French in college, so I scanned the room for Haitians. At one corner sat a dark-skinned couple. The woman was a severe and striking beauty, like Angela Basset if her cheek bones were even sharper and her eyebrows more starkly drawn. She wore a perfectly fitting peppermint-striped blazer; beneath her neatly creased pants her high-heeled patent-leather shoes glowed discretely. The man beside her looked a decade or two older. His face was softer, and his clothing was neat though not elegant. They stared straight ahead, speaking neither to each other nor to anyone else. I could not catch their eye.

Instead, I took a seat across from a young woman wearing hospital scrubs. She smiled and nodded when I asked her “Parlez-vous Francais?” I think I told her I was there to offer support, but who knows what my garbled grammar and accent communicated. She said she was from Aeety, and when I looked puzzled, she repeated “Haiti” in English. “Perhaps we should talk in English?” she asked, after explaining that she spoke English, French, and Spanish. I apologized, but she said, “We can try French if you’d like.”

What followed was a slow and patient French lesson, during which she listened to me intently, corrected my grammar, and responded, with a gentle smile, to my efforts at conversation. She learned that I taught at a university. I learned that she worked as a CNA, a certified nurse’s assistant. Her cousin was a New York City nurse. She was born in August – a Leo. She had been working in the U.S. for several years. She had arrived at immigration court at 8 a.m., directly from her hospital shift that had started at midnight. I will call her Marie.

Contact made, I wasn’t sure what next to do. It was now around 9 a.m. My wife had overheard Marie speaking English. “How was my wife’s French?” she joked. Marie was diplomatic and said she could understand it. She mentioned again the long shift she’d just completed. “I can get you some coffee,” I said. She smiled and nodded, so I ran down to the ground floor snack shop. Fifteen minutes later, I found my way back to the correct immigration court waiting room, coffee in hand. Only then did I notice the sign about no food or drink in the waiting room. To disregard any sign within an immigration court waiting room felt risky. I hesitantly offered Marie the coffee. She smiled and said, “Sugar?”

I hadn’t thought of that – I don’t drink coffee and don’t use sugar in my tea. Of course I’d get her some – say two or three packets? “I’d like six, if you don’t mind,” she said. Back in the snack shop, I didn’t see any sugar packets – only Sweet and Low. The cashier pointed me to a big sugar jar, but there was nothing to transport it in. I took a plastic lid and poured sugar into it. I traced my path back to the correct court waiting room, dropping little sugar crystals along the way like an urban Gretel. Still no ICE. I proudly handed the sugar-filled lid to Marie. She stood to receive it. She was petite, just my height, and the short braids framing her face turned outwards like sun rays or, in keeping with her Zodiac sign, a lion’s mane. She smiled, took the lid, and asked, “the stirrer?”

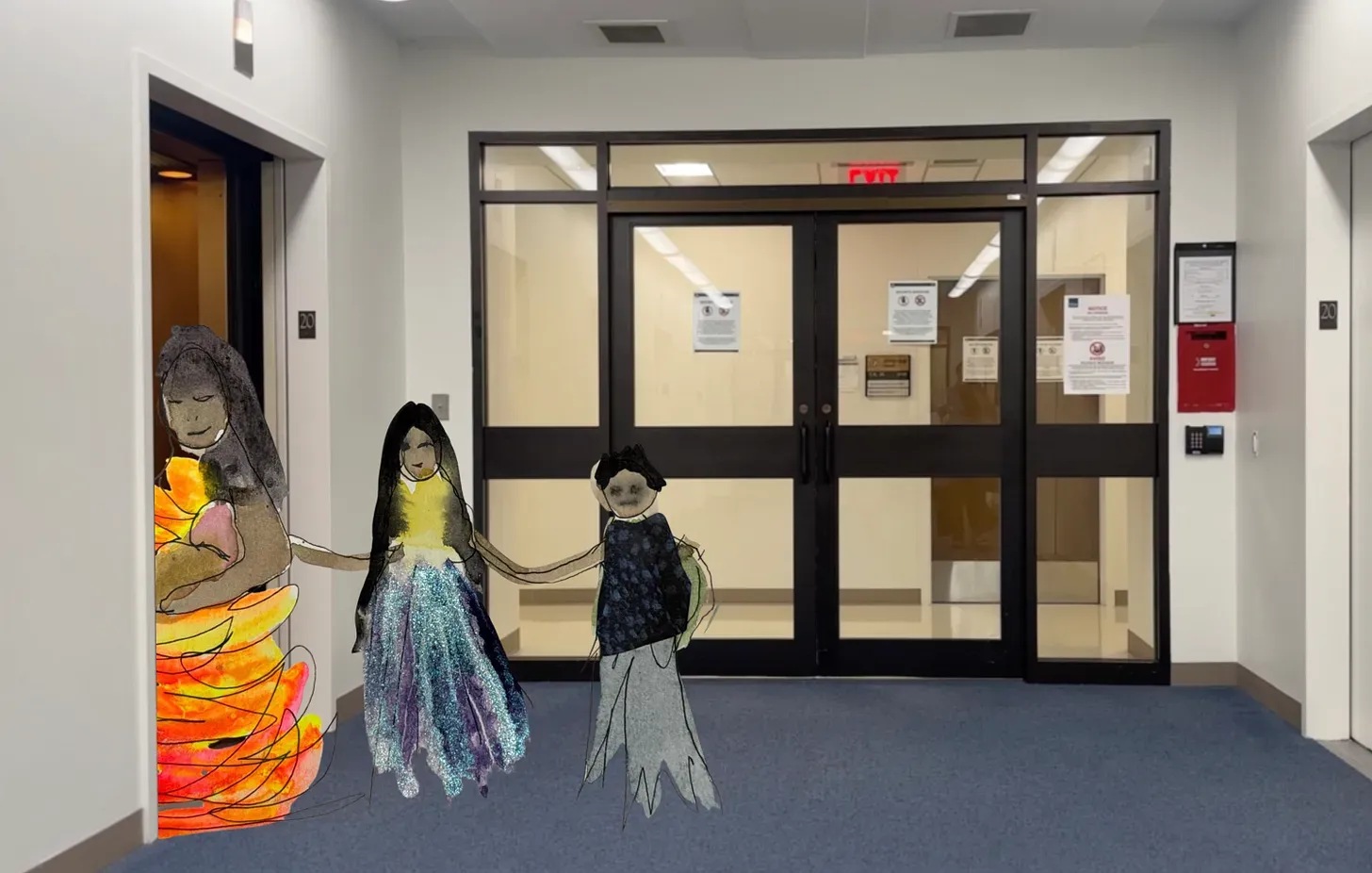

Of course I hadn’t thought of that. I apologized, shrugged, said I hoped she could make do. She tipped the lid of sugar into her coffee, rotated the cup, and thanked me for my trouble. She sat down and sighed. By now it was around 11 a.m. Marie chatted with some women sitting nearby, helping one interpret a court document written in English. I checked the hallways for ICE. Not a soul. The mood in the waiting room was getting looser. An extremely polite girl, around 10, watched over her three-year old sister as she scribbled on pieces of paper. The child’s exuberance as she showed adults her drawings made us feel human.

I asked Marie if her job was hard. “I can handle the job,” she said. The trouble was her love life. She’d left someone behind in Haiti – a woman she still loved. Her partner made it to the U.S. a bit later, but circumstances forced them to live in different cities. In New York she was dating another woman. Marie’s long-term partner didn’t have a problem with this, but her New York lover was exhibiting concerning signs of jealousy. Women! We shook our heads as I watched my wife, just back from her own tour of the floor – still no ICE – offering more colored crayons to the three-year-old. My wife had sensed Marie’s queerness immediately – hence her pointed reference to me as her “wife.”

“Was it OK to date women in Haiti?” I asked her. “It’s done,” she told me, “but it’s not easy.” This was one reason she had to leave. But going someplace where she would be free to love who she loved had forced her away from the love of her life. That was the contradiction. She had to leave because she loved, and then she ached because she left.

By now it was just after noon. My wife asked for something from the snack shop. Back down I went. I pulled a sandwich from the snack shop fridge and thought about the people in the waiting room. They had been there since 8 a.m., and still not one person had been called. I returned to the waiting room with a bag full of food. Again, I had forgotten that food and drink were forbidden in the waiting room. Again, there was not an ICE agent in sight. People gratefully accepted every item in my bag, including the sandwich I’d bought for my wife, which I offered to a distraught Latino father. He grimly accepted the sandwich without looking at me.

The three-year old ran back and forth. Crumbs and bits of food wrappers fell to the floor, each one a small act of resistance. Marie rested her head against the wall, her eyes shut. People spoke quietly to one another. Most remained in the seats they’d been in since 8 am.

Finally, at 2:30, something happened. A court employee said the judge would be seeing everyone, now, all at once. Everyone filed into the court room. Still no ICE presence on the floor. The only people left in the waiting room were me, my wife, and the neatly dressed man who had sat silently beside the woman in the peppermint blazer since 8:00 that morning. I asked him how he was doing. He said, “Well, it’s been a long day.” He told me he had been in the U.S. for 30 years, since he arrived from Haiti in the 1990s. He was an engineer. He and his wife had just bought a house in Long Island, though he wasn’t sure he wanted to leave Brooklyn. No, the woman he had sat with was not his wife. She had come recently from Haiti, he said, and no one she knew could advise her. He helped her fill out her out immigration papers, and then took a day off work to accompany her to court. I offered him a newspaper I’d had in my bag all morning. He thanked me and buried himself in its pages.

Suddenly, at 4:30, the court door opened and everyone filed out. Still no ICE. Not one person was detained. The air was popping with relief. The woman in the peppermint blazer was all smiles. She and the engineer left together. The Latino man held his child in his arms, his face exhausted but drenched in relief. Marie walked out with an older Haitian woman. My wife and I accompanied them out of the building. I hugged Marie goodbye, holding her a few seconds too long.